by Warren Bobrow | Mar 10, 2023 | Employee Engagement

For some of those who struggled the most with work from home (WFH), the biggest issue was a loss of the social connections they have at work. While introverts may have been celebrating, others missed their friends or “work spouses.” A work spouse is a...

by Warren Bobrow | Mar 3, 2023 | Employee Engagement, Talent Management

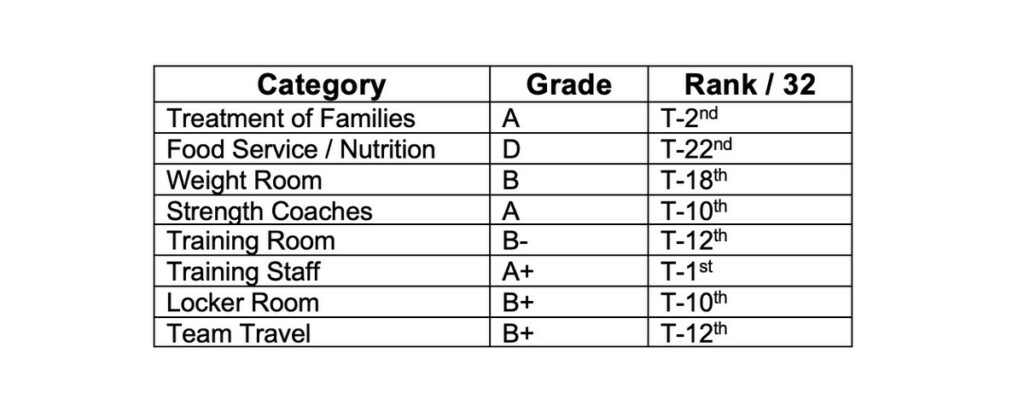

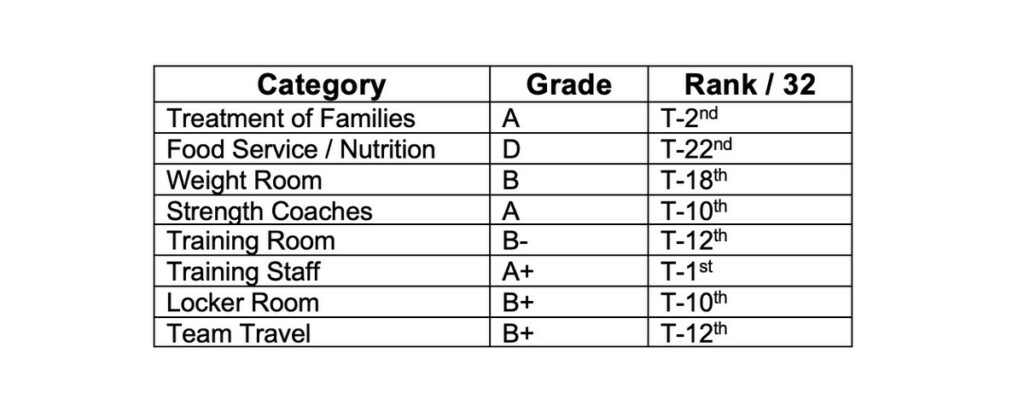

This is the time of the year where the National Football League (NFL) goes into radical feedback mode. Many (but not all) college players participate in The Combine, a physical abilities beauty contest where they also get interviewed multiple times by their...

by Warren Bobrow | Feb 20, 2023 | Employee Engagement, Pre-Employment Test Validation, Pre-Employment Testing, Talent Management

We have all seen and heard about how artificial intelligence (AI) is making great strides into different areas of life and work. Most recently, these advancements have made their way into creating art, writing, and other human interactions. Customer call...

by Warren Bobrow | Jan 3, 2023 | Employee Engagement, Managing Change

It’s the time of the year where futurists make predictions (we really need more follow-up on those) and big proclamations are upon us. Among these I’ve been reading are, “Work has changed forever!” and “Is this the end of the 9-5 workday?” The implications of the 9-5...

by Warren Bobrow | Nov 9, 2022 | Culture, Employee Engagement, Managing Change

Since offices have been opening back up, some, but certainly not all, employers are coming up with various schemes to get people to return to the office (RTO). Per usual, companies are looking at this more so from their perspective than that of their employees. But,...

by Warren Bobrow | Apr 22, 2021 | Culture, Employee Engagement, WFH

As working age people have been getting their COVID vaccinations in the US, companies are moving from the theoretical regarding the “new” work life into putting new policies into place. There are a few I want to point out because they may be indicators of...